MAURIZIO D’AGOSTINI: THE SAGA OF EXISTENCE

“… like a wave, which attempts to create a lasting image of itself, repeating itself in the wave that follows it: that’s what the entire life of a sculptor is like.”

Arturo Martini

“My work has always stemmed from things I found appealing and from my own personal experience and, in the end, everything worked out positively …”

In these words, Maurizio D’Agostini reveals not only his basic attitude and the approach underlying the conception of his works, but clearly indicates the fundamental aspect of his freedom of expression: a freedom which was not exactly a simple affair for a sculptor that worked during the last two decades of the 1900s.

It was a century which, on the one hand, began with the “dynamic explosion” of Umberto Boccioni’s work and futurism and, on the other, with the almost “supernatural” work and influence of Constantin Brancusi, which lay beyond the common sense of time and space and any specific location. Between these two poles, there was Pablo Picasso’s multilingual eclecticism, which, although considered above all for its decisive influence in painting, was capable of offering, with equal visionariness and in the form of a rough outline, an important series of variants in sculpture, using all the pickings he could put together, and “reinventing” them for the purpose of providing them with a plastic function.

Maurizio D’Agostini started out as a sculptor, and this can be said in the anthropological sense. His earliest work as an engraver and his costant surrendering to the fascination of the materials he has worked with – various metals, bronze, clay and stone – show that this is an artist whose thoughts and ideas are expressed through sculpted works: an artist who lives by moulding the worlds that fill his thoughts as he lives from day to day, and dreaming only those dreams engendered in his imagination. Thus, experiences of life and his dreams are interwoven and blended and are in turn reborn to acquire new forms in stone, clay, metal and bronze. Thoughts descend into the material world, passing through the master sculptor’s hands, becoming a separate and external alter imago defined in the process of materialisation.

In a critical review which he wrote in 1997, Stefano Ferrio refers to a “blissful innocence” apparent in D’Agostini’s work. In this sense, the artist’s world is brought into being by pure necessity, by a kind of “natural succession” that induces him to crystalise in material form his moments of reflection and by the “elementary spontaneity” of cause and effect, which allows him to appease and assuage his visionariness, transferring it into sculpture.

D’Agostini’s world is reassuring. Silent and far-removed, there are no visible, strident contrasts here: his figures seem to possess and outwardly convey an inherent certainty and strength. We have moved beyond the labouring of daily life and its misery, violence and affliction. Smooth and soft, these forms accompany his original intent, making it both real and tangible.

D’Agostini too has studied the 20th century. He saw the works of Brancusi and those supreme efforts made in an attempt to promote the cause of an Absolute Sculpture, in which the “descriptive” and superfluous are reduced to a minimum (“Cosmic Bird”, 1998); he studied the work produced by Arturo Martini and his admirable terracotta “descriptions” of life and nature; and he incorporated the surreal vein of Novello Finotti, but without absorbing his more disturbing and metamorphic side. However, the artist he spent most time carefully studying, and always surrendering to his inner impulses, was definitely himself.

Almost all of the exhibited works and most of those produced over the last thirty years are offspring of the small sculptures made using the pebbles and stones he went out to collect from the dry riverbed of the Brenta towards the end of the 1970s.

Ever since then, the artist in nuce did nothing else but follow his own instinct; he chose his own path, examining and reflecting on his feelings. If we examine those pebbles and stones, that is where we will still find the entire inner dimension of this artist. The pebbles reflect the simplicity of his relationship with the earth: an aspect of his nature which must have led him to live and work in his house-atelier in the village of Costozza in the Colli Berici (‘a beautiful, tiny, historic village surrounded by luxuriant green hills in the province of Vicenza’), where he feels perfectly at ease surrounded by familiar sights and things, immersed in a benevolent natural world with which he can easily communicate and protected by a light that never betrays him.

Much has been written about Maurizio D’Agostini, about his talent and his skills, about his search for an “absolute” reality, which would appear to involve everything and everyone, about his superior motives and intentions and, in other words, about everything that every artist could ever hope to attain, and might possibly achieve, at least in theory. In practice however, artists do not really exist in wild, far-removed dimensions: history itself looms in the background and will eventually determine the degree of their reliability and the seriousness of their research. To aspire to public standing and recognition as an artist is rather different from occasionally writing poems in an exercise book when we are schoolchildren. We’ve all done that. After that stage, we all made our decisions and followed our chosen individual paths. Far too often, we find such expressions as “absolute”, “poetics”, “purity” employed in common parlance to denote or qualify features and aspects of practically every imaginable field of human enterprise, from advertising to the cinema, cultural activities, art: they are thus emptied of their intrinsic value and lose their meaning.

Maurizio D’Agostini owes his artistic vein to his simplicity, to an urgent need to express and reveal his inner world and to the courage which induced him to abandon the reassurance and certainty of a profession for the uncertainty of a mission. The price to pay in this case – as we have just said – is uncertainty, while the advantages are freedom, visibility and the pride in one’s capacity to express something quite exclusive. Well, that’s the way it is at the outset; then, there’s the other side of the coin. There is a price to pay in releasing works of art to public scrutiny: one is “measured” and judged against the objective reality of both those who have preceded us and our contemporaries.

In this respect, D’Agostini is rather lucky, and he has considerable resources at his disposal.

From the 1980s onwards, there has been a growing pictorial trend that has gained a sure footing in the collective imagination, apart from becoming well-established in the market and amongst art critics. Over the years a growing number of talented fringe-group artists has gradually been establishing itself on the editorial staff of the magazine Frigidaire, along with Tanino Liberatore, Andrea Pazienza, Filippo Scòzzari and Stefano Tamburini, the virtuosi and forerunners of the “Nuovo Fumetto Italiano” [modern Italian comic-strip art]. Introducing a very new, “direct” and less academic background – linked more to “oral” rather than literary traditions – such newcomers as Marcello Jori, Massimo Mattioli, and Giorgio Carpinteri have invented a new creative dimension, which can be associated with popular American “low-culture” art forms.

Moreover, in recent years we have witnessed the triumph of a fantastic, Gothic dimension and the chivalrous denizens of oneiric worlds that can be related to Tolkien’s saga the “Lord of the Rings”. In the world of art, the event can be compared with the decisive impact which Beat Generation writers Ferlinghetti, Kerouac, Ginsberg, Corso and Burroughs had on literature in the early 1960s. The driving force which constituted the artist’s source of creative inspiration was thus replaced. High intentions derived from all-embracing systems, philosophies and religion were no longer the decisive factor: the points of reference were now everyday life, children’s stories and comics, neurotic and compulsive behaviour, trends, deviations, dreams, conflict, fears, and uncertainty.

And it is precisely here that we find Maurizio D’Agostini’s own creative roots: in stories that tell of worlds typified by sincere, immediate impulses rather than cultural codes and a universe of dogmas; in dimensions where intuition is all-important and more highly prized than mere rationality. Whether or not we are on the brink of a third world war, in D’Agostini’s sculptures we enter a world of dreams. The faces he has wrought present us visions of ineffable sweetness: images each one of us would like to have seen at least once in our lifetime. But they do not belong to this world. It is this world – happy in its having become manifest – which thanks him every day: it beckons him and daily repeats its signs of gratitude for its having been allowed to emerge, materialise and exist. Then an infinite, skyward gaze and purity appear as an attitude, reflecting memories of stories linked more to the Holy Grail, the Knights of the Round Table and Sir Lancelot and Guinevere than the atom bomb or mass destruction.

Maurizio D’Agostini translates into material form the stuff of his dreams and – perhaps even as he goes gathering pebbles from the Brenta riverbed – what he would still like to experience in his own life and see realised in everyone’s life, his foremost desire being the presence of a complete, all-absorbing, absolute figure of femininity. Hence there emerges an immense love felt for a chosen companion, chivalrous sentiment, respect for one’s opponents and the hope for a better future. In every moment of every day, the titles of his sculptures speak of such dreams: the “Vestale in Riva al Mare”[Vestal Virgin on the Seashore], “Il Re e la Regina”[the King and the Queen] and “Il Sogno del Cavaliere”[the Knight’s Dream] conjure up fleeting, hovering visions that reassure him and us too. His “Volo Cosmico” [Cosmic Flight], il “Viaggio verso l’Ignoto” [Journey towards the Unknown] and “La casa dell’Anima” [the Home of the Soul] relieve us from vulgarity and banality, our fears of the future and all forms of ugliness that may surround us.

Incredibly, D’Agostini’s sculptures seem to have been created in a time beyond our own: before politics, before television, before the degradation we are forced to witness and are incapable of redressing. But for us that’s wonderful! Let’s board the sailing ship of our “Navigatore solitario”[Solitary Seafarer], let’s listen in awe to the ecstatic melodies of the “Suonatore del Vento” [the Wind Player], and let us wait on the pleasure of the “Regina”[the Queen], happy to think that such an imaginary dimension might still exist, and in which an individual – the artist – is thus capable of subverting normal reality.

Sufficing unto himself.

Beatrice Buscaroli

Dedicated to Maurizio D’Agostini.

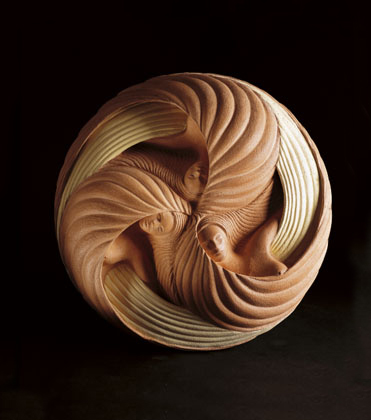

The soul, wonder and pity within the sphere of life and its rotation. Thoughts intertwine with the tenuous sign of spirituality to develop the sacral wisdom which influences D’Agostini’s works. D’Agostini creates with an ingenious need for regalness, universality, sacredness. The faces of his works are untouched by time, they almost reach space, they become a dream of indefiniteness, and in his “creatures” he always seeks to break away from precision.

A sculpture which makes us hold our breaths in all manners of existing and being.

Vera Slepoj

The Astronomer.

An astronomer with blindfolded eyes is not normal. Isn’t a wide and piercing vision the best attribute for someone you imagine to be absorbed in observing the stars? In the end, however, having blindfolded eyes does not mean that you cannot see. We understand that our man is well gifted with the necessary qualities, but his field of observation goes beyond the starry vault, extending to internal worlds, the worlds of thought, intellect and, even more, the world of the soul, being, infinity, eternity… As they are so vast, nothing can express these worlds better than a symbol: this is the meaning hidden behind the sphere of exotic marble placed on his knees.

Draped in his “renaissance” clothes, this astronomer lived for many years in the garden of a Savoyard villa where he interrogated visitors with his sibylline voice.

After a while, his effigy appeared on the covers of books, because he became the symbol of a French publisher, “Les Editions de l’Astronome”.

Léo Gantelet